- Press Office

- Shop The Gift

- Sponsorship

- TALK | ARTISTIC HERITAGE AND DEAF PEOPLE

- TB BOARD | INTERVIEW TO SHAFEI XIA

- TB BOARD | INTERVIEW TO THE ARTIST - ALICE TIPPIT

- TB BOARD | INTERVIEW TO THE ARTIST - DAFNA MAIMON

- TB BOARD | INTERVIEW TO THE ARTIST - GIOVANNI KRONENBERG

- TB BOARD | INTERVIEW TO THE ARTIST - MAYA ZACK

- TB BOARD | INTERVIEW TO THE ARTIST - NOEL MCKENNA

- [== Prev ==] [== Next ==]

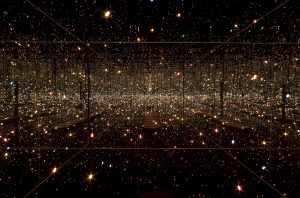

Yayoi Kusama, Fireflies on the Water, 2002. Mirrors, plexiglass, lights, and water, 111 × 144 1/2 × 144 1/2 in. (281.9 × 367 × 367 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Postwar Committee and the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee and partial gift of Betsy Wittenborn Miller 2003.322. © Yayoi Kusama. Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

[== LINK ==]

Yayoi Kusama. Infinito Presente

17 NOVEMBER 2023 – 21 APRIL 2024

Palazzo della Ragione, Piazza Vecchia, Bergamo

Press Office

CLP Relazioni PubblicheMarta Pedroli

At the exhibition The Gift. On life and death there is a shop section: The Blank has created the perfect box for art and culture lovers. The boxes contain works by Andrea Romano and Alberto Garutti, the latter an artist known in Bergamo for his famous work Ai nati oggi, an installation in Piazza Dante in collaboration with Papa Giovanni XXIII hospital.

The shop includes:

– gift tube n1: tube + a coloured paper of the work Didascalia by Alberto Garutti, 45 x 65 cm + a multiple of the work From me to .give by Andrea Romano, 50 x 70 cm + a ticket for the exhibition Il Dono. On life and death;

– gift tube n2: tube + a coloured paper of the work Didascalia by Alberto Garutti, 45 x 65 cm + a multiple of the work From me to .give by Andrea Romano, 50 x 70 cm + two tickets for the exhibition Il Dono. On life and death;

– catalogue of the exhibition previously opened at Palazzo della Ragione, Il Corpo Insensato, curated by Stefano Raimondi;

– personalised The Blank bag (black or white);

– personalised The Blank grey sweater;

– single empty tube.

Yayoi Kusama, Fireflies on the Water, 2002. Mirrors, plexiglass, lights, and water, 111 × 144 1/2 × 144 1/2 in. (281.9 × 367 × 367 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Postwar Committee and the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee and partial gift of Betsy Wittenborn Miller 2003.322. © Yayoi Kusama. Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

[== LINK ==]

Yayoi Kusama. Infinito Presente

17 NOVEMBER 2023 – 21 APRIL 2024

Palazzo della Ragione, Piazza Vecchia, Bergamo

The exhibition is promoted by The Blank Contemporary Art and the Municipality of Bergamo as part of Bergamo-Brescia Italian Capital of Culture 2023.

The exhibition Yayoi Kusama. Infinito Presente is made possible by:

Contribution of

- Camera di Commercio di Bergamo

Social inclusivity partner

- Brembo

Participation as Main Sponsor of

Support as Main Partner of

- Banca Generali Private

- Gruberg S.p.A.

- Magris Group S.p.A.

Sustain of

- Alias (Design & Furniture)

- Art Care (transport, production and setting up)

- Carminati Adv (Media Partner)

- CLP (Press Office)

- CVO GROUP (Security Partner)

- Linda (Cleaning Partner)

- Merlino (Kids Lab Furniture)

- Mida Ticket (Ticket Office)

- Phillips (Technical Partner)

- Achille Pinto (Educational Partner)

- Settecento Hotel (Accomodation Partner)

- Skira (Publishing Partner)

- Zenato (Wine Partner)

Event Partner

- Alluminio Agnelli

- ANIMA Sgr.

- Dielle Ceramiche

- Evelyne Aymon

- Palazzo Monti

TALK ARTISTIC HERITAGE AND DEAF PEOPLE: OBJECTIVES AND ROUTES FOR ACCESSIBILITY AND PARTICIPATION

The conference Artistic heritage and people: objectives and paths for accessibility and participation aim to disseminate and enhance the best accessibility and inclusion practices in museums in Italy and Europe and to promote contamination and the exchange of ideas between operators and International interventions.

The interventions of museum professionals from the Carrara Academy of Bergamo, Castello di Rivoli Education Department Museum of Contemporary Art, GAMeC – Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art of Bergamo, MAMbo – Museum of Modern Art of Bologna, Museum BeGo – Benozzo Gozzoli di Castelfiorentino, Tate of London, we will illustrate some of the main international projects dedicated to making museums spaces accessible to people.

To these are added industry experts such as Carlo di Biase, professional for cultural and museum accessibility, Consuelo Agnesi, architect, consultant and trainer on accessibility, Raffaella Carchio, psychologist, Enrico Dolza, director of the Institute of the Deaf in Turin , Elena Aparicio Mainar, consultant for cultural accessibility of MNCARS and MNTB (Madrid) whose interventions aim to deepen some fundamental elements for a conscious construction of spaces, initiatives and accessible educational projects.

The conference is aimed at museum operators, educators and all professionals in the cultural sector, to share experiences, methodologies and tools for inclusion, in order to guarantee the accessibility of places of culture to the deaf public.

The appointment expanded the objectives of LISten Project, the project aimed at increasing the accessibility and inclusion of the deaf public to the cultural planning of The Blank and to the contemporary artistic heritage, promoted by The Blank Educational and conceived in collaboration with Ilaria Galbusera , Knight of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic for his commitment to spreading knowledge and including diversity.

The LISten Project is carried out with the patronage of ENS and with the support of ASM Foundation, Cariplo Foundation, Pio Istituto dei Sordi, Regione Lombardia.

INTERVIEW WITH SHAFEI XIA

ELISA MUSCATELLI

Elisa Muscatelli – How would you describe your art practice to a first-time audience? What ideogram would you use to represent it?

Shafei Xia – The impressions of life, that’s what I go to draw. Three years ago I was a bit down, I wanted to paint, and I saw a paper that I had brought from China on the table. At the Academy with professor Caccioni we had a lesson about the body, and I drew food, the body, and sex all together in a pleasant environment. My professor liked it a lot and suggested me to continue on this path, this would have been the theme I would have had to investigate for two years, but I left it and started painting oil on canvas, inserting some funny elements. Then I met a boy, fell in love and all the emotions started coming out of my heart. Enjoying life, joy, I don’t have defined research that I have to follow, it’s all life’s thoughts and experiences, there is nothing to research.

The first work I did three and a half years ago, there is the written idiom 滿漢全席 (Manchu-Han imperial feast), it is a kind of view, I have to continue research of this nature, in this artwork you see the body inside plates, excrement and a bird, the bird comes sometimes back in my works, it means freedom. This artwork is about a celebration in an old Chinese palace, about a hundred dishes all together and all of them different, that had to be cooked.

In the first work I did on sandalwood paper there is a woman suffering, without a body, with only a bone. Then I added some Chinese symbols, mountains, in ancient Chinese paintings you always see a small mountain in the background in the distance, then I put the red element that is the is fire, and finally the clouds.

EM – Tigers, fish, sex acts, the composition of your artworks is fascinating thanks to the balance between erotism, humor, and reverence. How does the impulsive force of eros play into this?

SX – The tiger is a symbol of violence in love. The fish is freedom, in China, there is an ancient philosophy book about the symbolism of fish and birds written by Zhuāngzǐ, and the tiger is the symbol for violence. I have also always painted the fruit of the peach, which is a symbol of sex, it has a red color and I like it very much to eat. The ship is another symbol to represent freedom. The fish, the ship, the sea, they all mean freedom. In one work I paint this woman with a fish head who is sick with a mountain tiger, in another, there is no tiger, but there is still the presence of an animal taking a bone, it represents violence.

Make warm I did it quickly in one night, I was cold. It represents a quieter moment of my life, it is not like the initial passionate and violent love, after time there is calmer. First I painted the woman, then the tiger, then slowly the fire, the clouds, and the candles. It’s like taking a path through the heart. Sometimes there are no other meanings, some elements are just for beauty.

The symbol of sex, the tiger, and eating together always represents enjoyment, the act of taking pleasure.

I also like music very much, singing, the piano, but I have no knowledge about it and I sing badly. In Welcome to my show the tiger represents me, I am always a bit funny, everyone is serious about the concert and I represent myself in this way, I am like that in life too.

EM – Your Pinterest account looks like a little digital Wunderkammer: dollhouses, photographs of butterflies, and circus performers. What do these elements have in common in your collection?

SX – It’s all material that I deal with and that has had an impact on me. The dollhouse seems to me something joyful but also sad, it’s a closed environment that you can’t enjoy. The circus is also present in the collection and is a theme in my work.

EM – Shaoxing, Shanghai, Bologna: how are these cities reflected in your work?

SX – I don’t do anything in my native country, in Bologna, in Italy I learned to enjoy life, in China I have never done so, it’s all too fast, everyone thinks about earning money, not everyone but most. In Shanghai there is memory, I feel well, I met important people in my life: a German lady with whom I worked for two years and then an American lady who helped me a lot. A city is a place where I met these people, it’s the people I met in Shanghai that are the most important thing.

EM – Except for Fellini’s aesthetic, which has been for you a historical, literary, or cinematographic reference of great impact in your artistic and personal career?

SX – Fellini doesn’t influence me that so much, I like his personality, his films. In my opinion, the first influence is Henri Matisse, then Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. I don’t know the perspective, when I started studying art I met Henri Matisse and Vincent van Gogh and some women artists, then Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and then a great artist, Sanyu. Their life was honest and that is important for your life. For example, Sanyu never liked to have collaborations with the gallery, unlike other artists who wanted to, he always maintained his position, had many relationships, enjoyed, traveled, left everybody. He was not a person who was at home always painting or looked at art as something serious, he lived more seriously than art.

Another reference is William Somerset Maugham, who wrote The Moon and the Sixpence. When I finished my three-year course I went to work and read his books. The book is about a boy who doesn’t want to become a normal person but wants to find his own freeway.

INTERVIEW TO ALICE TIPPIT

Claudia Santeroni

INTERVIEW TO DAFNA MAIMON

Elisa Muscatelli

Elisa Muscatelli – How would you describe your artistic research to a new audience approaching to it for the first time?

Dafna Maimon – I like to create experiences that tell stories about how we are put together, how we deal – or don’t really deal – with our emotions, our bodies, and each other. Usually, my works start from an experience, often a frustration, a sense that things could be different.

Exaggeration is a way for me to communicate those feelings. I then look for other stories, images, theories or techniques that both support the original spark, or in fact counter it, broaden it. Then I try to put it together into something that becomes an experience for an audience. Our wrestling with loss, and trauma, our individualist constructs of reality as a whole, and the systems we’ve put in place to operate this reality (patriarchy, consumerism individualism, etc), and our not being in tune with the underlying reality as it is, (for a lack of better words, “the flow of things”), is an ongoing conversation in all of my works.

EM – In your works there are many researching topics and the humor is an interesting point of view for reading them. How important this approach is and how does it influence the realization and the experience of your works?

DM – It’s important to have some lightness, to be playful, otherwise it feels like just more science, “facts”, and perspectives that are bound to be too limited. Work can be play, and when it feels like it, that is usually when I’m doing my best work. Humor is a way to connect with people, but it’s not something I try to do by force, it’s just that usually I don’t have motivation to make anything that doesn’t make me laugh, whether it’s a kind of laugh propelled by sadness, absurdity, or pure joy. Laughing together, and laughing alone, are maybe the most important things. It’s an eruption, like crying or orgasming; humor is just my favorite go-to and the most communal one.

EM – Often, in your performances, as in Wary Mary, Eat All You Can or Opps Hoops, there are universal images, from the womb to the solar system, to the childhood world.

Are these the starting points of your performances, or the landing places of your research?

DM – They are usually starting points, but not always. 🙂

EM – The space, in your works, is essential: from time to time, the viewer is dropped in prehistorical caves or into the kebab and falafel’s restaurant Orient Express, reconstructions which create a short circuit of time.

How important is the relationship with the space and the time inside your artistic practice?

DM – Since, I’m really intent on creating very vivid experiences, the space plays a big role. It allows me to create a super specific world in which the experience occurs. Ideally, I would swallow the audience and block off anything that’s distracting from the sensation I’m trying to awaken. Also, I love physical things: sculptures, objects, costumes; the different textures that help express a story into something that is not just cognitive or linear, but sensed. There’s time inside the piece, and then there’s the time it reflects or talks about. Mostly, I like to mix signifiers of different times, and I tend to be more excited esthetically about creating images that are timeless or not necessarily super contemporary, even though contemporary issues are at stake. In terms of time inside the works, I tend to want to sedate people, and gravitate towards repetition and working with loops, so it’s more about expressing states of being that feel ongoing.

EM – Your artistic practice deeply explores woman’s figure, seen as generative being: of fear, of another life, of new ideas. How do you place this vision within a social artistic panorama divided between a strong feminine activism and a pro gender fluid struggle?

DM – Well, the idea of “a woman”, or gender, in general, is a construct, but since my works often start from (non-fictional) women I know, or historical figures, the work reflects on the many stories of those who have lived female lives, and what they have encountered. I’ve always had a hard time “understanding my gender”, and the associated roles, so a lot of the work also comes from there, this reckoning with this female gender. So, I don’t see those (strong feminine activism and a pro gender fluid struggle) as necessarily countering each other, I’m super excited about all the change I’ve already witnessed in my life, and the firsthand experience of women supporting each other now much more. I also think about starfish a lot, some of them can change sex back and forth, that feels really logical.

EM – In your performances, languages belonging to different media, from the theater, to the cinema or scenery, intersect each other. How do you perceive the interaction of these languages and what is your relationship with them?

DM – In what I do, they just intersect as needed to communicate whatever I’m trying to communicate. I enjoy exploring the different possibilities within them. I have no previous relationship really to any of them, or any kind of particular training, or any one approach, I just try to work in as many ways as possible, so I learn things from each language, and it’s history. The exploring of each helps support each, and provides different entry points and flexibility to work within the different languages. For instance, that I used to work more with video, and the logic of editing, has had a really fun/good effect on the way I work with performance, and now I’m hoping that the more recent work with performance and the body will do the same when working in video again.

INTERVIEW TO GIOVANNI KRONENBERG

Laura Baffi

Laura Baffi – I can honestly say you are one of the artist I’m very fond of, so to speak. I vividly remember when in an exhibition I saw, for the first time, your works. It was in that occasion that I got to know you. I was stunned by what I saw, because your works were extraordinarily close at the artistic path I was approaching at. From that moment I have followed all your exhibitions (both personal and collectives) with keen interest and I can say that the affinity I perceived from the very beginning has never disappeared. Despite this, I ask you to briefly describe your work.

Giovanni Kronenberg – I don’t have formulas or “statements”, in fact I think we should seriously stop pedantically filling them in. I think it’s not up to the artist to tell or to illustrate his work. It’s quite absurd to ask him to make questions or hypotheses – through his works – and then to give the respective answers or certainties. The artist can transmit some more information, but he is a spectator of his work like all the others and like all the others he is subject to the mystery and secrecy that his work contains. To be honest I don’t even like to quote, but there’s a well known quotation that may be appropriate: “This, today, is all that we can tell you: what we are not, what we do not want.”

LB – Generally speaking, you always work on small-size dimensions and you prefer, on the overall view and the monumentality, an art based on detail research. Throughout acts apparently simple, you do micro – or macro, depends on the point of view – operations that modify the naturalness of the matter you are observing at. As if, scooping up the remains and making them your own, you attributed at the object another sense, innate, but otherwise unexpressed.

Where do the objects you collect come from and which, after transforming them, you expose?

GK – I don’t know if I work with small dimensions. I work with real, honest size. The objects I use are like this. I can say for sure I don’t force my works towards a gigantism that I have always found nauseating, gratuitous, useless. In a conversation, if it has a normal course intended as sharing or comparison, there is no need to shout. Then of course you can even go so far as to scream and beat, but it’s not a dogmatic or standard condition. I often think that the most famous and mysterious painting in the history of art – the Mona Lisa – is a little bigger than 50 x 70 cm.

I work on details because the objects I use have a strong polysemic charge and it wouldn’t make much sense, in my eyes, to twist them in the hope of adding more. I consider the art I propose an art of revelation and this is manifested, most of the time, simply through minimal – sometimes even transient – movements. The objects that I collect and propose as works often come from chance encounters, but other times from precise ideas and will. Over the years I have established relationships with people who submit these artifacts to me. I try to evaluate their formal and material possibilities and if I think it’s worth it, I try to put my hands on them and work with them.

LB – Your works express a rustic openness, but among the materials you make use of, there are often precious stones. Most of the pieces you use come from the natural world as well as they are poor or rich materials. Richness that isn’t ostentation, but elegance, refinement. How could we interpret the use you make of gold?

GK – For me, the elegance of the work is one of the most important challenges to work on. By elegance I don’t mean a state of subjective vanity, but a spiritual dimension, capable of isolating the work and enhancing its pathos and secrecy. Gold – for me only present as a very thin gold leaf, used both in sculptures and drawings – is an inevitable and recurring passage and landing place in my path, if you think that in the last 10 years I have worked with materials like silver, malachite, agate, ivory, porcelain, rock crystal and many others. I am also fascinated by its use in the history of art, because I perceive its tradition and therefore a comparison.

LB – Do you know what wabi-sabi is? I briefly describe it, to help the reader too: it’s a way of seeing things, especially in their transience, typically Japanese and derived from Buddhist teachings. Essentially it consists in attributing value to an extremely imperfect and/or incomplete definable element, in opposition to the Ancient Greek ideal of beauty. In wabi-sabi the defect becomes a characteristic, a peculiarity. In fact, the practice that best defines it, it’s “kintsugi”, where the fragments of a broken ceramic are welded with gold, embellishing it from an economic point of view, and also because it becomes an unique piece. It is said that wabi-sabi, in addition to a sense of beauty, releases also a certain melancholy. Mostly according to wabi-sabi, beauty is inherent in what is old, withered and deteriorated. Untitled (2019, dried leaf, golden marker) is, in my opinion, a representative work. Time has in fact a fundamental component in your work: the objects from which you begin, belong to another Era, they are withered, in some cases fossilized. What is your position on the relationship between Art and (im)perfection?

GK – My sculptures often bring together very distant times, in no way associable or approachable. Once they are reinserted in the “here and now” as works of art, they level out times and distances. I didn’t know the wabi-sabi thing, but it seems to me a modality actually similar to some of my working practices and suggestions.

Many of the works I made are literally the result of chance; some of them manifest themselves through transience. Pathos, mystery, secrecy, spirituality: the characteristics that I look for in artworks do not derive from exactitude or perfection.

INTERVIEW TO MAYA ZACK

Elisa Muscatelli

Elisa Muscatelli – If you had to sum up in three keywords the aim of your artistic research, which would you use? And why?

Maya Zack – Archive, memory, encounter.

One of the ways i can articulate the research-question which is at the base of my work is: “What is a living memory?” and “How can we create a living memory?”. My work develops out of the fear of forgetting and the experience of loss and disappearance. How can we live after something was cut off? How can we know it ever existed and how can we remember it? Whether I’m thinking of my own mother who died when I was 21 years old, of childhood of each of us or the event of the Shoah.

This is also the mission of the feminine character in my film Counterlight, an archivist in a fictional archive dedicated to the Jewish poet Paul Celan. In the film, she turns from an archivist into an alchemist, an ‘alchemist of memory’. She takes the ‘dead memory’ of the archive – tables, figures, maps, recordings, photos, poems and other documents in black ink on white paper – and tries to resurrect it, to create out of it the ‘memory golem’, a living memory.

She is inventing her own ‘memory-science’; leaving the regular traditional archival work and moving towards a subjective creative approach that puts her in a bold artistic dialogue with the poet. As a result of this she starts intervening with the past until she reaches the point of the trauma and transcends into primordial realms…

EM – Often your works face the theme of memory in relation to the human being and its collective history. Do you think common memory is fundamental for the personal identity buildings?

MZ – I think of collective memory as a point of reference and as an enriching pool of knowledge I like to be in a dialogue with. I also think common memory is inevitable – be it common memory that finds its roots in actual events, memory we are born with which is stored in our body and psyche such as archetypes, or be it collective memory which is embedded in our language.

In my art I like to address historical cases which are broader than my own experience, and through this I seek to decipher my own relation/dissociation with the circles I supposedly belong to.

My own family which is a mixture of various geographies, histories and destinies (i.e. Jewish immigrants form east Europe with holocaust background who came to Israel and a Catholic partly-indian grandmother from Venezuelian Andes with possible marrano roots) contributed to the fact my sense of belonging was never a natural, stable, nor obvious to me, it made me realize that my story could have been completely different.

The epistemological concern regarding our personal identity finds an answer in Hebrew where the words community (עֲדַה), witness (עֵד) and testimony (עֵדוּת) share the same linguistic root.

EM – Do you think that your works could be more easily perceived by a public living in a deep and personal way the Jewish culture? Or do you believe in the power of an universal message with no exceptions?

MZ – I believe in works which are multilayered, that can operate in few modes and provide various kinds of messages which come together to construct a complex artistic imagery.

I try to design the work in such a way that it will have an impact on a universal-human level as well as to communicate on particular levels and arouse various fields of knowledge which are relevant for the work.

EM – This interview has been done in an unusual historical moment, in which in social media #stayathome goes crazy, the lockdown changes the spatial boundaries and the home dimension is taking on new features. A lot of your works presents a home environment, that becomes a dynamic space where stories and images of the past and elements of the reality live together. How do you cope with the concept of home and home environment?

MZ – I don’t find the current situation so strange as for me the home is and always was the universe in many ways, a bubble from which I communicate. The concern with home, domesticity, interiors and how it blends with the work/art is in the foundation of my work. E.g. in Mother Economy (1ts part of the trilogy) the ‘home’ plays part as the ‘crime scene’ with the objects around the space as forensic evidence, the laboratory of the ‘detective’ is the kitchen and the place where the final results are presented is the dining table and the final equation that sums up the investigations – is an economic pie chart – served to the table as a sliced Kugel (Jewish traditional round noodle pudding).

And vice versa, in both Black and Wite Rule and Counterlight, the feminine characters (scientist and archivist) are in their working place, they live and exist there only.

EM – A woman who escapes the time control in Counterlight, dogs that seem to release themselves from the imposed orders in Regola in Bianco e Nero, a well educated housekeeper who catalogues domestic objects in Economia Madre. In this trilogy of memories with a layered narrative, the order, accompanied with memory, seems to be the central idea. How does the concept of order establish itself in such different works? Which work can be considered the trilogy’s spin-off?

MZ – All parts of the trilogy are based on the tension between the side of the orderly, factual, objective, empirical, scientific, bureaucratic, actual and the side of the chaotic, hermeneutic, subjective, pseudo-scientific, sensual, artistic and magical.

The principle of order in the works is accompanied by a sense of desperate meticulousness and obsession to endlessly document – as if to preserve the information and save it from being lost – a means to control the chaos and cope with the trauma and with my fear of forgetting, on a personal and collective level.

The project I’m working on these days (which includes a video, a book, drawings and an installation) can be described as a spin-off project, it continues my concern with memory but instead of dealing with the dry and ‘dead’ archive-memory I am now addressing the memory which is in the body, which has to do with liquids and moist.

EM – The memory…a term which echos in your works almost imperatively, I would ask you what we never should forget…

MZ – We should never forget that everything is to be forgotten… but also that we can still find a way to connect to the absolute, the eternal, the other kind of memory, maybe the matriarchal memory which is not documented in the patriarchal order and is born out of that oblivion.

Noel McKenna

2020

Oil on plywood

42 x 44 cm

Courtesy the artist and Mothers Tankstation gallery Dublin and Niagara Galleries Melbourne

[== LINK ==]

INTERVIEW TO NOEL MCKENNA

Claudia Santeroni

Claudia Santeroni – If you should summarize your artistic research in a few lines, how would you describe it?

Noel McKenna – My artistic research is just part of my everyday life most of the time as I have a philosophy that inspiration can come from anything. My day to day activities often provide ideas for work.

CS – The picture you chose for our newsletter is a glimpse of a street you can perceive the sea from. While I’m writing this questions, in Italy rage the pandemic (I wish from the bottom of my heart that, when this interview will be published we’ll be out of this situation) and this ‘outlet ’behind the curve, this marine vision at the end of the street seems very auspicious.

NM – The image Road by Sea came from a photograph I took in Wellington while driving around with a friend. The Sea I enjoy just looking at, people are not made for the sea unlike fish, whales and other marine creatures. In the painting the road which has been cut through the rocky hillside is an interesting visual: composition. My working method is quite quick, paintings this size 42 x44 cm are mostly done in one session and instinct is what I rely on, I like to keep a freshness about the final image.

CS – What role do the animals play in your work? I’ve read that your first exhibition had been built by animals etching and so far they have been really present in your life, mates of your home daily life. In an 2001 exhibition, if I correctly understood, you carried on enamel on wood various ‘lost pet signs’.

NM – Animals I have always been close to from an early age, having been a quite lonely introverted child. The first animals I became attached to were stray cats in my childhood home in Brisbane which I used to feed by buying tinned cat food with any pocket money I had. I witnessed quite a few generations of kittens being born, would have had a dozen or so in my backyard, making my parents angry.

I do have friends, I am married with two boys but is interesting with the “social isolation” we are practicing now, my life has not changed that much I often have spent long periods never leaving my home, studio except to go the supermarket. Animals I use in my work for different reasons, firstly I enjoy looking and studying them, they generally are at the mercy of people and my experience has been with domestic animals, cats, dogs and birds but while not believing their thoughts are as complex as ours I believe their is a lot more going on in the minds of animals then people think . When I moved out from living with my parents I did not have any pets in any of the houses I lived before I married my wife Margaret which was a period of about 8 years. Since being married have only had dogs due to Margaret being allergic to cats. It is hard to imagine not having a dog in my life. I had an exhibition of lost pet posters which was based on posters people had put up when their pets were lost. Most were ones I saw around my area in Sydney plus a couple from trips to Melbourne. Often people’s text they put on the poster is quite emotional, often I think put down quickly in order to get the message out there. I never changed the text people wrote but did ring the phone number that was on poster to see if animal was found and to see if ok to put their number in my painting. Most people did not object to having their phone number on the painting.

CS – I liked DOOR series: the painting on everyone of it, made me think about possibilities beyond the limit.

NM – The door series is an extension of my interior paintings which is a big part of my work. The holes I cut into the doors then put back into the holes with painted images of domestic life behind the closed doors kind of came from when I visited a nephew and he had on his door a handwritten sign “Ceep Out”.

I enjoyed the misspelling and never asked him if it was deliberate. A room, home is a shelter from the outside world, and I often think about what goes on behind closed doors, could also be connected with my love of Hitchcock’s movie Rear Window.

CS – A piece really struck me: Police helicopter, Central Park, N.Y, 1986. Most of the other pieces seems to me extract of “normality out of extraordinariness”, this one instead from my point of view is a unique case, because it shows an exceptional event.

NM – Police Helicopter Central Park was done after my first trip to NY in 1986, I did it from a photograph in the NY Times which I cut out and bought home. I have lost the cutting and cannot remember the story behind the photograph. I loved NY immediately on being there and have been going on yearly trips for about the last ten years or so. It is a combination of the great museums there as well as just walking around the streets always seems to be something interesting to see. The city though has lost a bit of the mix of life that was there due mainly to gentrification of areas but still has enough left to be interesting.